The poem below—“Frederick Douglass” by Robert Hayden—is one of my all-time favorite poems. I love the passion, the directness, the emphasis on physicality, the confident assurance that someday things will be different—not if but when. I love the way Hayden brings concepts like freedom and liberty down from the abstract into the flesh and blood world. The poem is not about freedom in general but about this freedom, this liberty—a freedom and liberty that are clearly present in the world. But, as the poem beautifully articulates, it is not available to everyone (the poem was written during the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s). I love the weariness of the word “Oh.” I love the description of freedom and liberty being beautiful but also terrible (depending on what we choose to do with our freedom and liberty).

Thank you, Robert Hayden, for your exquisite poem!

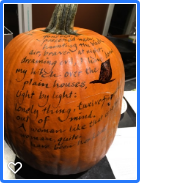

Frederick Douglass

When it is finally ours, this freedom, this liberty, this beautiful

and terrible thing, needful to man as air,

usable as earth; when it belongs at last to all,

when it is truly instinct, brain matter, diastole, systole,

reflex action; when it is finally won; when it is more

than the gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians:

this man, this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien,

this man, superb in love and logic, this man

shall be remembered. Oh, not with statues’ rhetoric,

not with legends and poems and wreaths of bronze alone,

but with the lives grown out of his life, the lives

fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.

– Robert Hayden (1966)