I requested Into English: Poems, Translations, Commentaries (Minneapolis: Graywolf, 2017) after reading Marissa Lingen’s capsule review. This anthology (edited by Martha Collins and Kevin Prufer) is indeed my kind of thing: twenty-five poems in a variety of languages, from Ancient Greek to Haitian Creole, accompanied by three translations, followed by an essay about those translations by another translator who sometimes adds their own. I remember almost nothing about the Aristotle class I took in college with the late Eugene Gendlin, but his advice to consult more than one translation of any text when possible has stayed with me throughout the years.

Interlibrary Loan finally wants the book back. I was able to keep it long past the original due date because of the pandemic, so there was time for it to accumulate some of the bookmarks that populate many of the other volumes in the house:

So, what were some of the things I wanted to remember?

page 8: “History doesn’t only efface a text – it also builds ever-changing scaffolds of meaning around what is left.” —Karen Emmerich, commenting on translations of Sappho fragments (98a and 98b)

page 22:

“Returning to the Farm to Dwell” is a landmark poem by Tao Qian (365–427). It is the first in a series of five poems and celebrates a return to a simple life in the countryside. For over a decade, Tao Qian worked as a government official, but he felt constrained and grew increasingly dissatisfied. In 405, Tao Qian retired to the countryside, where he farmed, planted chrysanthemums, drank wine, and wrote poetry. In cultivating his spirit, he became one of the early, great dropouts in the tradition of Chinese poetry.

—Arthur Sze

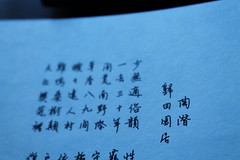

page 20:

From early days I have been at odds with the world;

My instinctive love is hills and mountains.

—the beginning of James Hightower’s 1970 translation

pages 20–23:

“By mischance I fell into the dusty net / And was thirteen years away from home.” —Hightower

“I erred and fell in the snares of dust / and was away thirteen years in all.” —Stephen Owen (1996)

“I stumbled into their net of dust, that one / departure a blunder lasting thirteen years.” —David Hinton (2008)

In all three translations, it’s worth pointing out differences in the poem’s numbers. . . . In line 4, all three translators choose to ignore the literal text, which clearly says “thirty years,” and use “thirteen years” instead. Hightower asserts that thirty years makes no sense; that the time of government service was probably close to thirteen years, and so he transposes the “ten” and the “three” (ten plus three, instead of three times ten). Owen and Hinton follow suit.

In contrast to these translations, I chose to retain “thirty years” and want to offer a justification. First, the text clearly says “thirty years”—no one disputes that—and, although thirty years is not literally true, there’s a figurative justification for it. “Thirty years” has shock value, and it’s also justifiable in that one can conceive of thirty years as half a lifetime. In Chinese astrology, there are twelve zodiac creatures and five elements (wood, earth, air, fire, water), so one cycle with each of the five elements requires sixty years. That cycle can be seen as a completed lifetime. I take Tao Qian’s phrase to mean that once one departs from the true path, it may take half a lifetime to discover it.

When I was young, I did not fit in

with others, and simply loved the hills and mountains.

By mistake, I fell into the dusty net

and before I knew it, it was thirty years! . . .

—Sze

Speaking of nets, it’s time for me to apply my own analytic powers to other people’s English and Spanish, so the rest of the sticky notes and scraps will have to wait for some other day.